Mercyhurst professor part of significant discovery

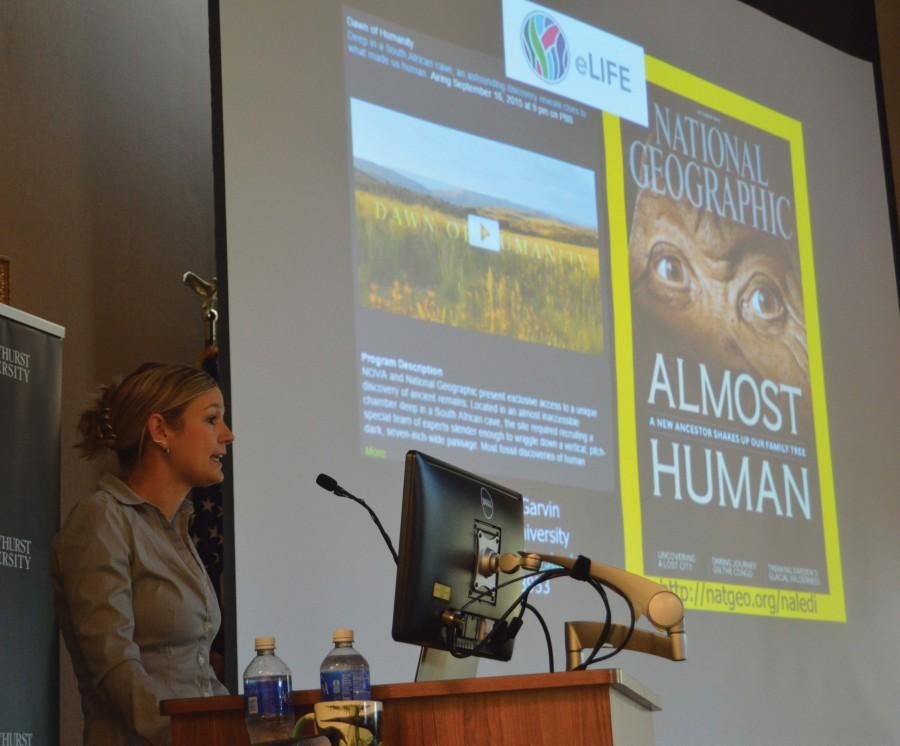

Heather Garvin, Ph.D., presents the National Geographic cover featuring ancient bones, Homo naledi

September 16, 2015

A Mercyhurst Anthropology professor was part of a monumental scientific discovery of a new species of hominins, or early humans, that was announced worldwide last week.

Heather Garvin, Ph.D., was part of a scientific team that examined ancient bones of what has been named Homo naledi. Her role was to conduct the month-long analysis of the hominin fossils found in South Africa, which led to the addition of the newest species of our human ancestral tree, Homo naledi, to be defined.

Over 1,500 specimens were uncovered in the excavation at the Rising Star Cave System, located near the “Cradle of Mankind,” a region of South Africa where many other hominid species were discovered. Generally, new species are defined using only a few specimens, even isolated jaw bones, but Homo naledi was different.

“The amount of material covered from this small area is extremely rare,” said Garvin. “The remains from at least 15 individuals representing both adult and juveniles were found.”

Instead of keeping the discovery to himself and analyzing the fossils on his own, Lee Berger, Ph.D., paleoanthropologist of the University of Witwatersrand, who was first told about the remains, organized a team of early career scientists and senior experts in the field to work together to describe and analyze the find.

“They decided they wanted to use this new, revolutionary technique,” said Garvin. “It’s a different mindset and hopefully it’s a pattern that continues in the field.”

While in the think tank, Garvin was on the cranial team, identifying, analyzing and describing the fragmented bones of the cranial region of the hominoid bones. Garvin used her own techniques and methods to figure out the brain size of this new species.

“I was also responsible for the 3D scanning of all the cranial specimens,” said Garvin. “It was actually my 3D virtual reconstructions that National Geographic artist, John Gurche, used to create his reconstruction.”

Garvin was also the leader of the body team. The body team’s purpose was to use their skeletal knowledge to estimate how tall Homo naledi would have been.

“Our role was to look at some of the limb bones and estimate how big Homo naledi was,” Garvin said.

To the team’s surprise, their analysis determined a height much taller than expected. Through analysis of the body size and cranium size, Garvin’s team discovered that Homo naledi had a larger body, but smaller brain.

“[Scientists in the field] used to think that body and brain size increased together,” Garvin said.

The combination of traits in this new species is one of the most important qualities of the new find.

“The combination of primitive and more modern, human-like characteristics in this new species is unlike any other known human ancestors and may change the way we think about human evolution,” Garvin said.

Both the muscle marking on the shoulders and curved fingers indicate tree-climbing habits within the species. However, the leg bones and feet indicate that Naledi walked on two feet. Once all traits were analyzed, the team began to wonder how these human remains ended up in this cave.

“The only explanation left was that they were deposited there intentionally by other members of their group,” Garvin said. This activity is seen as rare for a species with such a small brain size.

Garvin still has many unanswered questions about Homo naledi.

“If Homo naledi was depositing their dead deep in the cave, it suggests that such a behavior was completed with a relatively small brain,” said Garvin. “That they could have these human-like activities without a human-like brain.”

This suggests that scientists may have placed too much emphasis on the size of the brain in the past in terms of human evolution.

“They are going to continue exploring,” said Garvin. “Every fossil that we find just gives us another clue, another piece to the puzzle to help describe what our evolutionary past is.”