‘Voices of Transgender Children’ heard loud and clear at lecture

October 3, 2019

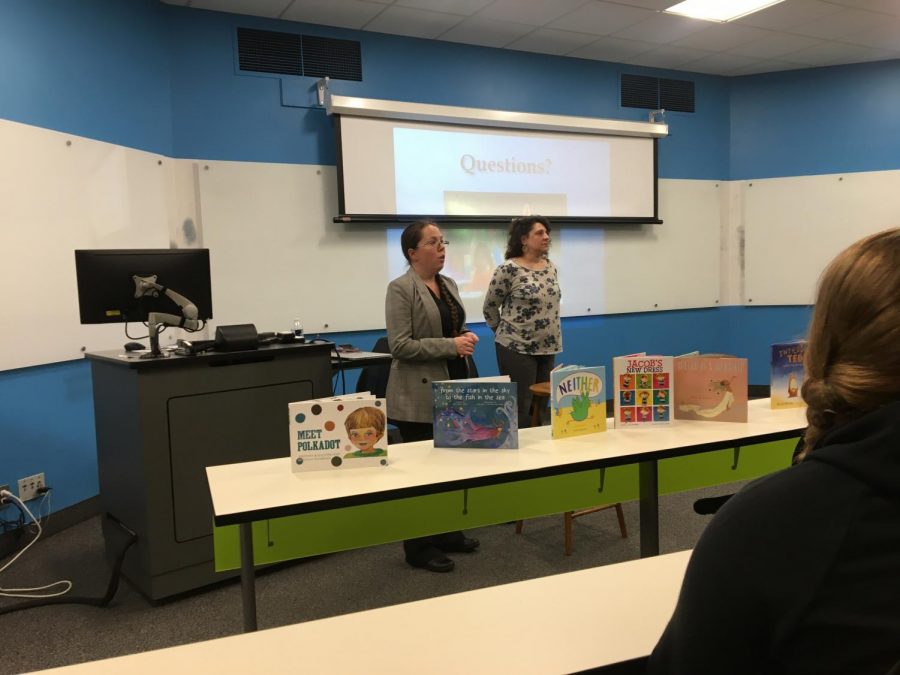

On Sept. 25, Ashley Sullivan, Ph. D., assistant professor of Early Childhood Education at Penn State Behrend, and Laurie Urraro, Ph. D., assistant teaching professor of Spanish, Languages at Penn State Behrend, presented the findings from their recent publication, “Voices of Transgender Children in Early Childhood Education: Reflections on Resistance and Resilience” to Mercyhurst students and faculty members in Zurn 114.

Sullivan and Urraro have spent the past decade studying the lived realities of transgender individuals and the educational systems and policies that shaped their experiences.

Sullivan’s research focuses on a variety of topics including social justice and equity in early childhood education, LGBTQ children and families, poverty studies and literacy development in toddlerhood. Prior to her position at Behrend, Sullivan worked as a kindergarten teacher, curriculum writer and professional development facilitator in Connecticut.

Urraro is currently a lecturer in Spanish at Penn State Behrend. Her areas of expertise and interest include modern peninsular languages and cultures, women’s studies, contemporary Spanish film, studies of gender and sexuality and contemporary Spanish theater. Prior to her current position, Urraro held teaching positions at Northwest Pennsylvania Collegiate Academy, Kent State University, Ohio State University and Gannon University.

The presentation covered many topics regarding sex, gender, sexual orientation and gender roles and the effects these have on the lives of transgender individuals. Data was represented in a variety of ways including charts, videos and personal stories from individuals interviewed for the book. The audience, which consisted mainly of education majors and minors, was also encouraged to participate and engage with the material by answering questions and reading provided statements out loud.

Sullivan began the presentation by defining transgender kids as, “kids whose gender identity and biological sex are not in correlation with one another.”

According to Sullivan, starting around age two, when gender identity begins to develop, these children start to notice and outwardly express that their biological sex does not match the gender identity they are being raised with.

The two researchers then went on to explain the difficulties in studying transgender individuals as there are no clear answers pointing to the reasons behind transgender identity. Alhough it is estimated that about three-quarter of a million school-age children are transgender, there is no completely accurate population size of the transgender community. They emphasized that this is due to a lack of overall support and a heightened sense of fear that the community faces every day in our society.

In discussing their research findings, Sullivan and Urraro highlighted three categories that transcended racial and socioeconomic background for their participants, who they referred to as “research partners”: social interaction, physical space and gender normalization.

The research question Sullivan and Urarro studied was how early childhood environments impacted their participants’ experiences in the transgender community.

A variety of social interactions, both positive and negative, were cited as deeply influential by participants. Friend and peer relationships as well as supportive teachers and parents had positive impacts of individuals. However, every individual spoke of experiencing some degree of bullying and violence in their school environments.

The physical spaces in which these interactions occurred often correlated with positive and negative experiences as well. For example, while many individuals expressed feelings of safety and acceptance in the library or within art and music classrooms, they often felt a great deal of fear and discomfort other areas of school life. Many faced disciplinarian problems in highly populated areas such as the gym or cafeteria, on the playground or in bathrooms and locker rooms.

Finally, body normalization played a huge role in the lives of those interviewed as many discussed their experiences with gender segregation, which takes the form of separate boy and girl lines or “boys against girls” class activities.

Additionally, the demand for “gender performativity,” in which individuals are expected to act as their assigned gender in the eyes of society, caused confusion and discomfort for students whose gender did not match their biological sex.

Each of these factors can have drastic effects on transgender individuals. According to Sullivan and Urraro, these negative experiences can contribute to mental health problems later in life. These problems include depression, stress related anxiety, self-harm, drug and alcohol abuse and poor self-image.

The two researchers ended their presentation with suggestions on how educators can normalize differences in gender and sexuality while also creating a more positive environment for transgender children. Some of these included abandoning assumptions, showing support, eliminating gender segregation in the classroom, involving parents and providing protection and safe spaces to students.

After the formal presentation, Sullivan and Urraro opened up the floor for questions from the audience and stayed behind to answer individual questions from students after everyone else had dispersed from the lecture hall.