Using science to breed small undomesticated cats

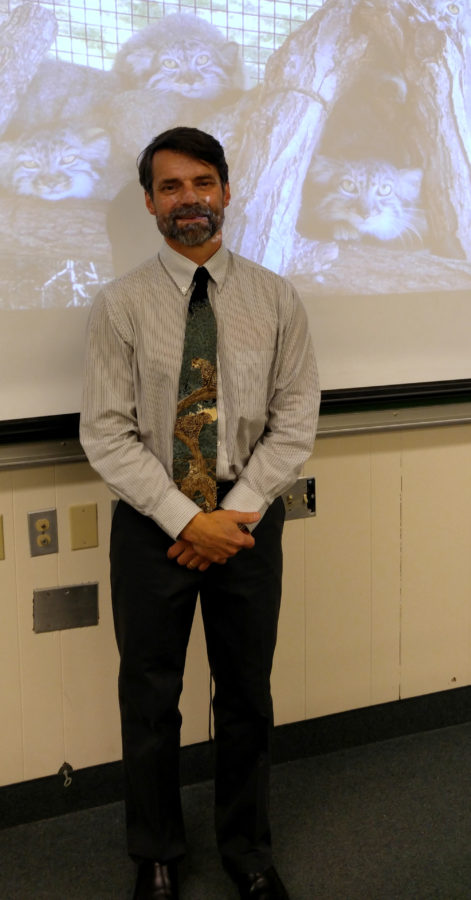

William (Bill) Swanson, Ph.D. in front of a picture of Pallas cats.

April 19, 2016

Artificial insemination sweeps the college.

On Friday, April 15, William Swanson, director of artificial insemination at the Cincinnati Zoo and Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife (CREW), gave a seminar on artificial insemination as part of the Christina Difonzo Biology Seminar Series.

CREW is an organization that specializes in conserving the lives of endangered animals all over the planet. Their current projects include polar bears, rhinoceroses, exceptional plants and felids, or cats. They are working toward projects on freshwater otters and amphibians.

Swanson works primarily with small, non-domesticated cats. There are 37 non-domestic cat types in the world. Most of them are threatened with extinction in the wild and are in critical need of improvement. Eighteen of those species, large and small, are maintained in North American zoos.

“I work with small cats because no one else does and [everyone] focuses on large cats for conservation,” Swanson said.

The small cats need conserved too.

He works primarily with five species of small cats: Pallas cats, sand cats, ocelots, fishing cats and black-footed cats.

“Most zoos cannot maintain their populations by natural breeding alone. Many species need the help of science to improve their populations,” Swanson said.

Natural breeding can have many negative sides such as the animals may not get along or tolerate each other.

Once, Swanson and his team put two cats together for natural breeding and the female had her arm mutilated by the male to the point where it needed amputation.

“She was still able to breed,” said Swanson. “But we did not want to risk putting her back with the male.”

This female was successfully inseminated and gave birth to a kitten.

To optimize captive breeding programs and to monitor hormones and cycles CREW uses gamete biology, cryobiology, endocrinology and ultrasonography. Swanson also gave characterizations of basic reproductive biology of these small felids.

One project that Swanson discussed was the Pallas cats in the Cincinnati Zoo.

Pallas cats only produce the hormones used to reproduce about three months out of the year, in the winter months.

It was discovered that the Cincinnati Festival of Lights held every year was actually causing the Pallas cats to have an even shorter reproductive cycle.

Swanson spent some time trying to fix this, before deciding to move the cats outside, which allowed the animals to cycle normally.

The kittens being bred outside unfortunately did not survive, as they were infected with Toxoplasmosis.

The zoo staff developed a plan to bring the kittens inside shortly after birth and raise them until they were strong enough to survive themselves. This plan also worked extremely well.

Swanson showed pictures of many of the kittens that have now been successfully bred using this method.

CREW works with many different projects to determine ways to artificially inseminate felids. All of their experiments are conducted on domestic cats before they are tried on the exotic ones.

Some of the issues that artificial insemination helps to suppress include: addressing behavioral or physical incompatibilities between the pair, connecting regional populations by transporting frozen semen and embryos, preserving genetic diversity and linking wild populations with zoo populations without having to bring more cats into captivity.

The second part of Swanson’s seminar was about the sterilization of feral, free-roaming cats in the community.

There are about 80 million free roaming cats in the United States. The goal of this project is to non-surgically sterilize these animals.

Some of the projects that are being worked on to help this are Gonacon, an injectable vaccine that makes antibodies to stop the production of gametes, which is already being used on the white tailed deer population in some areas. Its affects are not permanent yet.

The other method is gene therapy, this will also create antibodies but it would be injected directly into muscle cells. It would then use adenovirus to stop production. The latter of the two cannot replicate on its own and it will not integrate into the genome.

This seems like a very odd job, but Swanson’s reasoning for choosing this career path is great.

“I do it because I am a conservationist. I wanted to find any way I could to help preserve the cat population, I am passionate about keeping these species alive,” Swanson said.